Objectivists, libertarians, and Burkean conservatives alike can enthusiastically approve of tort law—the branch of civil justice enforced by court suits. In principle, it is one of the great achievements of a free society—a peaceful, lawful means by which citizens may seek redress for harms done to them, without resort to personal retaliation or political power.

For “ideologists”—in the best sense of that term—a powerful logic derives the system from moral responsibility, human rights, and the distinction between civil and criminal justice. I have a right to be left alone by individuals and governments—a right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Government should not supervise my choices by “preventive” law. But if I harm you, in a way that is not merely chance and not properly criminal, I am responsible for the consequences of my actions. We may settle it privately; but when we cannot, government provides the ground rules and the apparatus: laws, courts, and enforcement of verdicts.

For conservatives, such as admirers of the Anglo-Irish statesman, Edmund Burke, who recoiled from ideology and put his trust in historical experience, tort law is a great inheritance of the common law. It is not a system designed by theorists, but a body of practical rules refined through centuries of real disputes and concrete experience—an evolving social technology for holding people accountable while preserving liberty. By the second half of the 1760s, Sir William Blackstone was publishing his Commentaries of the Laws of England and his third book, “Of Private Wrongs,” devoted 27 chapters to types of private torts, procedures, and remedies.

In either view, tort law is fundamental to a just society. It embodies personal responsibility, the rule of law, and the basic idea that rights are not mere slogans but enforceable protections.

That should make us acutely aware of something else: the vital importance of a tort-law system that is just, efficient, and as nearly incorruptible as possible. Tort law that is perceived as equitable, fair, and affordable is indispensable to our sense that we can control our personal destiny under freedom.

And that is why so many Americans who would applaud tort law in principle today view it in practice with contempt—and more than occasionally with outrage. George Priest, Sterling Professor of Law and Economics at Yale, observed in the Journal of Economic Perspectives (1991), a troubling dynamic of modern tort practice is that “a disproportionate share of financial awards flows to attorneys rather than to those who were harmed,” distorting incentives and rewarding litigation rather than resolution. (One widely cited figure: $0.75 in transaction costs per dollar received by claimants.) The earnest faces of law firm partners are seen everywhere, now, recruiting lucrative cases. We’ve all seen the billboards, bench advertisements and the like: “Injured? Call Donte! 1-800-HURT-NOW,” and so on. In particular, those in mass tort-and-personal-injury law spend $100 million annually on digital advertising for clients; top firms like Morgan & Morgan spent more than $110 million on TV ads alone in 2024. These legal advertising costs increased 39% between 2020 and 2024, driving a surge in mass litigation. The selling point is not so much compensation as the possibilities of riches.

None of this is new. Yet, for reasons not entirely clear, the sustained public attention to tort law’s pathologies seems far less today than it was in past decades. In the 1980s and 1990s, runaway verdicts, malpractice insurance spikes, and mass-tort crises became recurring national stories. Think tanks such as the Manhattan Institute, and writers such as Peter Huber and Walter Olson, helped bring these issues into sharp public focus. Legislative reforms were debated seriously in state houses and in Congress.

The organized bar—especially the trial-lawyer lobby—proved to be a formidable opponent of many reforms, and for understandable reasons. Tort law is a massive industry and industries protect their revenue streams. Dick Weekly, founder and chairman of Texans for Lawsuit Reform (TLS), wrote in a 2023 op-ed: “For decades, America’s personal injury lawyers were a predictable political force. They funded Democrats, funded liberal causes, fought lawsuit reform, and built their fortunes in places where the courts treat litigation as an industry.” Still, one major national reform did pass in the modern era: the Class Action Fairness Act (2005), designed to curb abusive class-action practices, including venue shopping and the exploitation of uneven state-court systems. CAFA remains an important reminder that reform is possible when public awareness is high enough and political will becomes strong enough.

Whatever else tort law is today, it is expensive. It is expensive for everyone.

Whatever else tort law is today, it is expensive. Not merely expensive for corporations, doctors, universities, or newspapers (which, as President Trump reminds us, live under constant threat of suits). It is expensive for everyone.

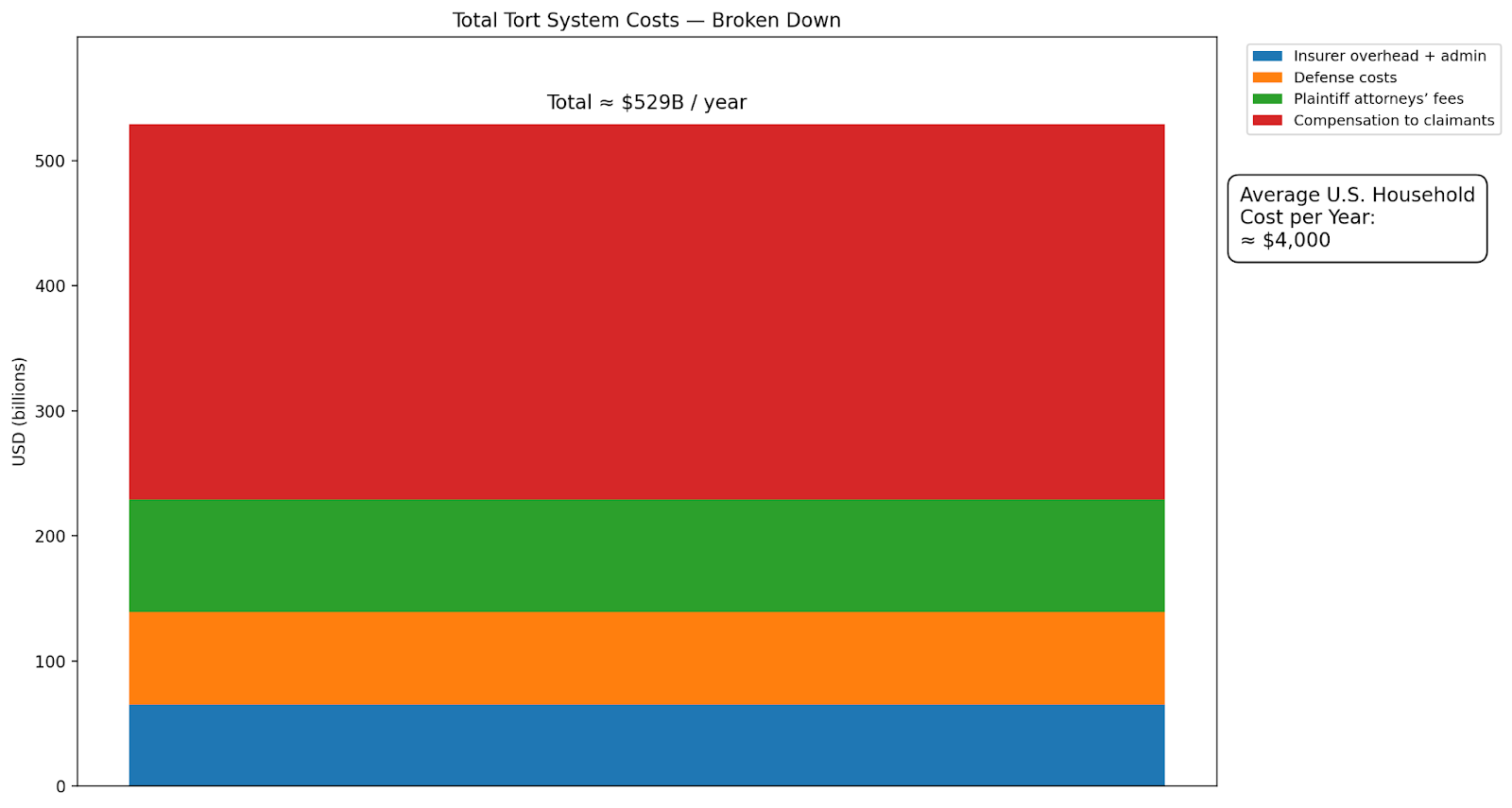

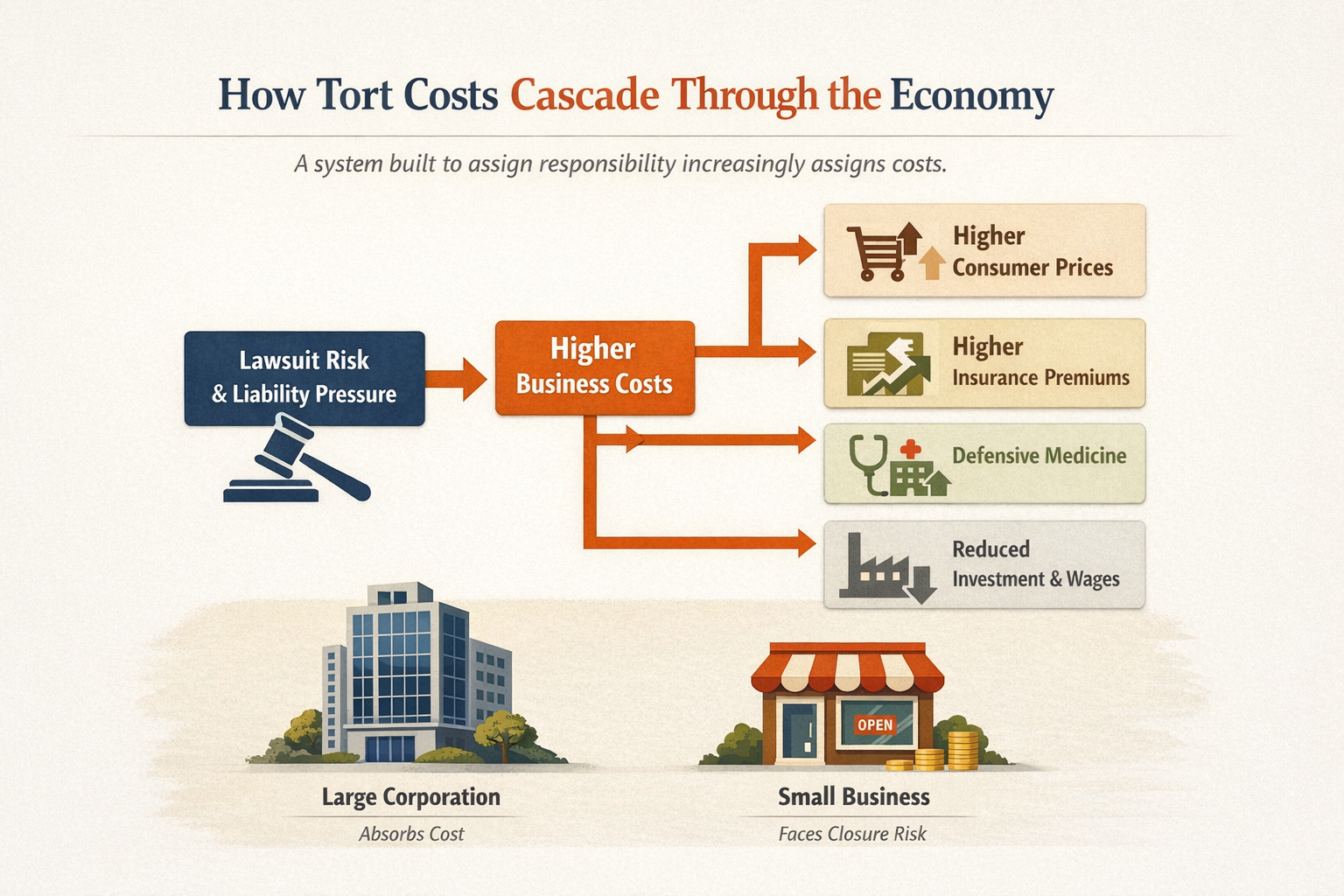

Estimates in the third edition of Tort Costs in America, published by the Chamber of Commerce’s Institute for Legal Reform, put the total economic cost of the American tort system at $500 billion per year, equal to 2.1 percent of U.S. GDP. Spread across the economy, this amounts to roughly $4,000 per household annually—a hidden surcharge baked into the price of goods, services, insurance, and healthcare. Nor are these costs stable: tort-system costs have been growing at rates above 7 percent per year, faster than inflation and faster than the overall economy. Businesses do not absorb these costs as a charity; they pass them along through higher prices, higher premiums, reduced wages, or reduced investment. To quote Dick Weekly of TLR again, before highly successful tort law reforms in Texas in 2023 (discussed in article #5), lawsuit abuse was “the No. 1 threat to Texas’ economic future.”

Tort costs are not simply money transferred from wrongdoers to victims. They are a form of national economic drag.

These figures include not only jury awards and settlements, but defense costs, administrative overhead, and costly compliance and risk-avoidance behavior. Tort costs are not simply “money transferred from wrongdoers to victims.” They are, to a significant extent, a form of national economic drag.

As Elon Musk has observed: “Current class-action law is actually a massive tax on the American people and desperately needs reform. It is one of the reasons medication is so expensive in the USA. Somehow, other countries do just fine without class-action law."

Doctors order tests not primarily to improve outcomes, but to avoid being second-guessed in court.

A clear instance is medicine. Malpractice liability not only raises malpractice premiums; it changes medical practice itself. Doctors order tests, imaging, referrals, and procedures not primarily to improve outcomes, but out of fear of being second-guessed in court. The result is defensive medicine—an enormous but difficult-to-measure cost driver that inflates healthcare spending.

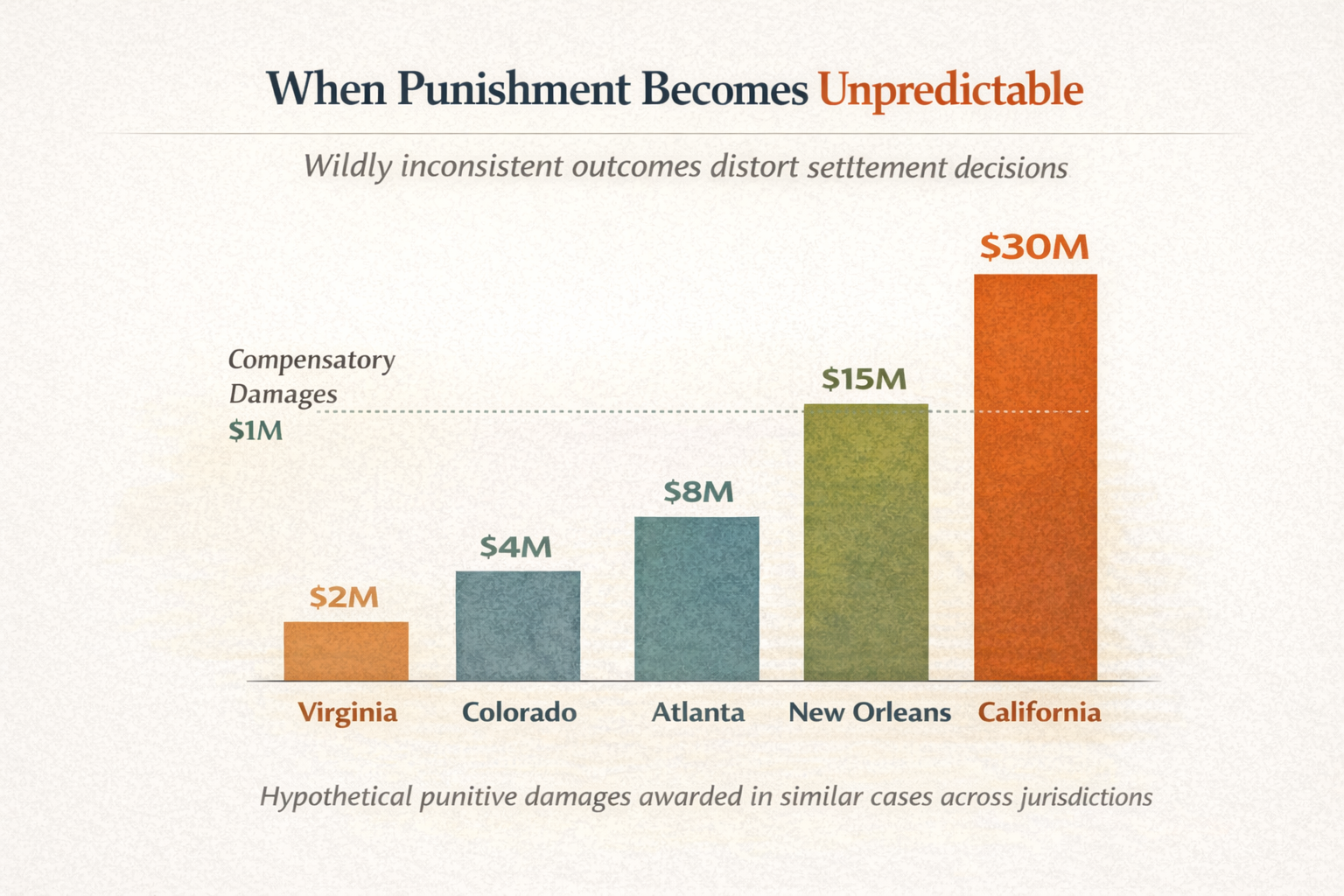

Another cause of public anger is the spectacle of punitive verdicts that dwarf compensatory damages and appear less rational punishment than moral theater. Punitive damages have a legitimate role—punishing reckless, malicious, or fraudulent conduct. But in practice, punitive awards can be wildly unpredictable, varying by state, venue, judge, and jury temperament. The American Tort Reform Association (ATRA) states that punitive damages by “frequency and size have grown greatly in recent years. they are routinely asked for today in civil lawsuits. The difficulty of predicting [them] . . . in any particular case, and the marked trend toward astronomically large amounts when they are awarded, have seriously distorted settlement and litigation processes and have led to wildly inconsistent outcomes in similar cases.”

A manufacturer can do everything reasonable, yet still face ruinous liability.

Worse, the modern expansion of doctrines like strict liability—under which defendants may be held responsible regardless of fault—tend to transform tort law from a system of responsibility into a system of collectivized risk. A manufacturer can do everything reasonable, yet still face ruinous liability because a harm occurred. A system built to assign responsibility for harm increasingly assigns costs.

We tend to picture “corporations” as the natural targets and victims of tort excess. But this misses a crucial point: proportionally, small business is often the bigger loser. Large firms can absorb lawsuits as a cost of doing business. Small firms cannot. Many suits are filed not because the plaintiff expects to win at trial, but because the mere cost of defense is enough to force settlement. That is not civil justice; it is gaming the legal system.

A concrete illustration of tort costs cascading through society—and how little the system exhibits of “compensation”—is the asbestos litigation saga. For decades beginning in the 1970s, asbestos claims became one of the largest mass-tort regimes in American history. Asbestos-related liabilities drove dozens upon dozens of companies into bankruptcy, and the bankruptcies in turn produced a network of asbestos settlement trusts. Today, these trusts are estimated at more than $30 billion, intended to compensate claimants.

Yet, detailed analyses of asbestos litigation and trust compensation repeatedly find that a large share of the system’s resources was consumed by legal fees, transaction costs, and administrative overhead, while claimants received a fraction of what the “headline” numbers suggest. Even when real harms exist—and asbestos harms are tragically real—the system’s structure can channel disproportionate gains toward the machinery of litigation rather than toward the injured.

The issue is not that lawyers make money; it is that the system increasingly rewards litigation itself rather than justice.

This is not a condemnation of profit or of lawyers. The free market is a profit system; it rewards those who create value. In abusive tort practice, the incentives are often reversed: the greatest rewards going not to those harmed, not to those who create, but to those “rent seekers” who exploit the system’s procedural leverage. The issue is not that lawyers make money; the issue is that the system increasingly rewards litigation itself, rather than justice.

The issues go deeper than policy. They are philosophical. Tort law is too fundamental to what we value most—objective law, a functioning justice system, and a culture of personal responsibility—to be left to the forces that too often shape it today.

Tort law expresses a basic moral intuition of civilized life: actions have consequences.

Tort law expresses among the most basic moral intuitions of civilized life: actions have consequences, “harm” is not a metaphysical accident, and that a person who injures another is not absolved simply because the injury was not criminal. Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., one of the great minds of American jurisprudence, put the principle starkly in The Common Law (1881): “The law of torts treats consequences as the natural measure of obligations. One who voluntarily does an act that naturally and generally results in injury to another must make good the loss.”

Tort reform is not an attack on justice. Properly understood, it is a defense of justice.

It is a principle worthy of a free society. That makes it matter that the system intended to instantiate it has become inefficient, unpredictable, and increasingly expensive. Tort reform is not an attack on justice. Properly understood, it is a defense of justice—against the corrosive incentives and institutional drift that threaten to turn civil responsibility into legalized plunder.

In articles that follow, we will examine:

—The grossly disproportionate “gains” from winning lawsuits sometimes with sensationally high stakes that go to attorneys rather than those harmed

—The black-belt level gaming of the system through venue selection and procedural leverage and what all

—Big payoffs for filing speculative lawsuits and extorting settlements

And:

—What can be done if philosophical clarity, public awareness, and political will come together again

Tort law is too important to get wrong. And the costs of getting it wrong are not borne by “corporations.” They are borne by every American who buys a product, visits a doctor, starts a business, or wants to risk inventing something “too” new.

„Walters neuestes Buch ist Wie Philosophen Zivilisationen verändern: Das Zeitalter der Aufklärung.“